Most months, I try to answer a well-focused question.

This month, however, I want to simply take a broad look at how FDA conducts its postmarket surveillance study program under Section 522 of the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. FDA published a new final guidance on this topic on October 7, 2022, and the agency also made corresponding updates to its database. That gave me the chance to study the data, however incomplete they are. More on that later.

Overview of the Guidance and the Program

Before I turn to the data, I thought it would be helpful to provide a high-level reminder of what FDA’s postmarket surveillance study program is all about. As explained in the guidance, Section 522 provides FDA with the authority to require manufacturers to conduct postmarket surveillance at the time of approval or clearance or at any time thereafter of certain class II or class III devices. I’ll talk more about the question of timing below.

Postmarket surveillance is supposed to be the active, systematic, and scientifically valid collection, analysis, and interpretation of data about a marketed device. FDA obtains the data collected under a surveillance order to help to address public health questions on the safety and effectiveness of a device.

The statute spells out the circumstances under which FDA can require one of these studies. FDA can require postmarket surveillance for a class II or class III device when:

- failure of the device would be reasonably likely to have a serious adverse health consequence;

- the device is expected to have significant use in pediatric populations;

- the device is intended to be implanted in the human body for more than one year; or

- the device is intended to be a life-sustaining or life-supporting device used outside of a device user facility.

To identify where it wishes to order a 522 study, FDA uses a variety of sources including adverse event reports, a recall or corrective action, post-approval data, review of premarket data, reports from other governmental authorities, or review of scientific literature. A 522 order specifies the devices subject to the surveillance order and the reason that FDA is requiring postmarket surveillance (i.e., the public health question(s)).

If you want to read more about the subject, the GAO did a review of FDA’s practices in ordering Section 522 studies in 2015. While the GAO report is a bit dated, it includes many interesting observations about the program.

FDA’s new and updated database has some significant limitations to it. For example, one of the main questions I have is how big the studies are, meaning, how many patients need to be enrolled. I was also curious how long these studies run, for which I would need a beginning and an end time. I was also interested in how successful the studies are at achieving completion. Unfortunately, the database includes insufficient information to answer any of these questions. Hopefully, though, you will read on because there is still some interesting information to be gleaned.

My Questions About How the 522 Program Is Functioning

How often does FDA order a 522 study?

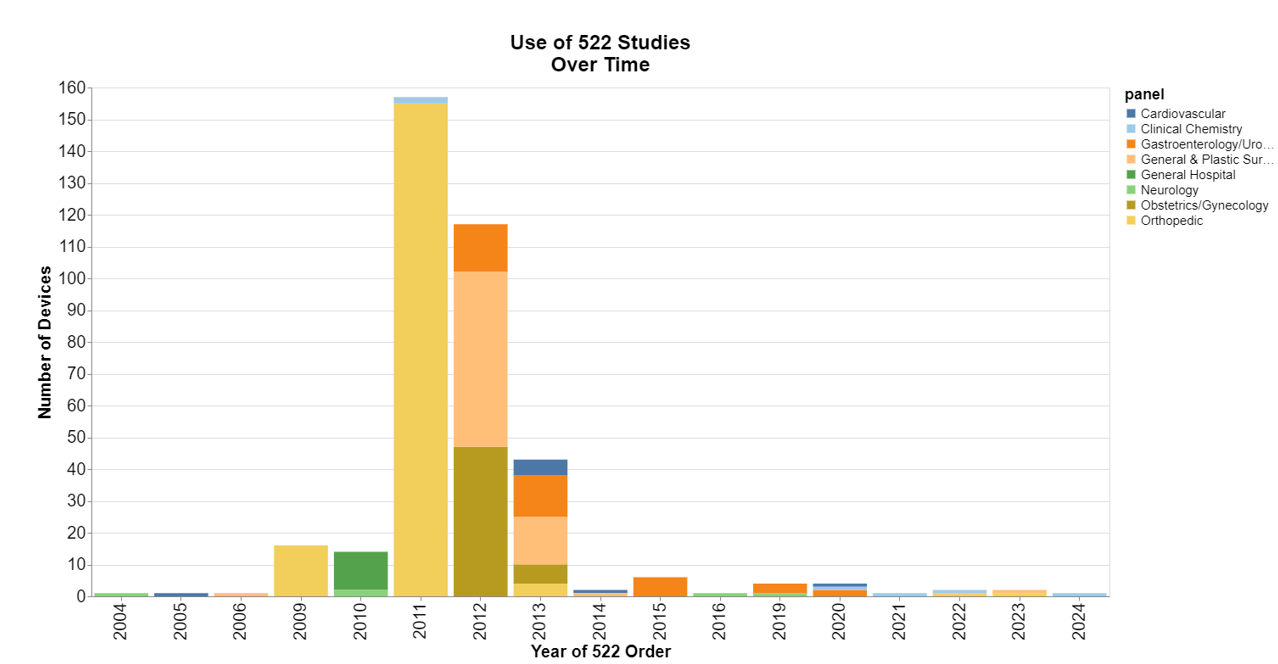

Turns out, most of the time, ordering such studies is not very common, but there were apparently some dark years around 2011 and 2012. If you’re old enough, you might recall that in 2011 FDA had safety concerns about metal-on-metal hip implants, including potential bone and tissue damage from metal particles. In 2012, FDA had concerns with implanted surgical mesh and other devices used in general and plastic surgery and obstetrics and gynecology procedures. 2024 is obviously only a partial year because I ran this data in July.

Typically, when does FDA order a 522 study in the life cycle of a medical device?

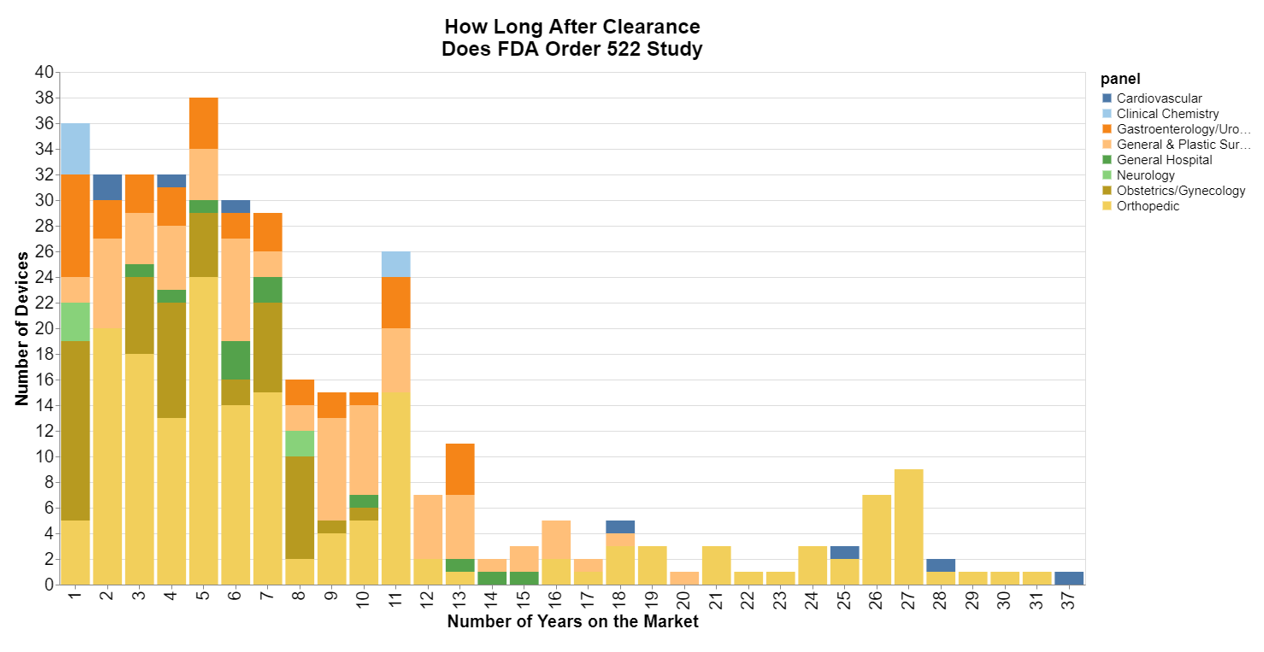

For this chart, I focused on 510(k) devices, and used as the start date the date FDA clears the product. This chart surprised me. I figured most of the studies were ordered soon after the product was cleared, so the longtail surprised me.

That said, it’s obvious the longtail mostly belongs to orthopedics, so again, in 2011 FDA ordered 522 studies broadly for many products that were on the market including those that had been on the market for quite some time. It also looks to me as though cardiovascular products were some of the older devices. The other parts of the longtail were general and plastic surgery devices, which was perhaps many of the mesh devices that were subject to 522 orders in 2012.

How many 522 studies are completed?

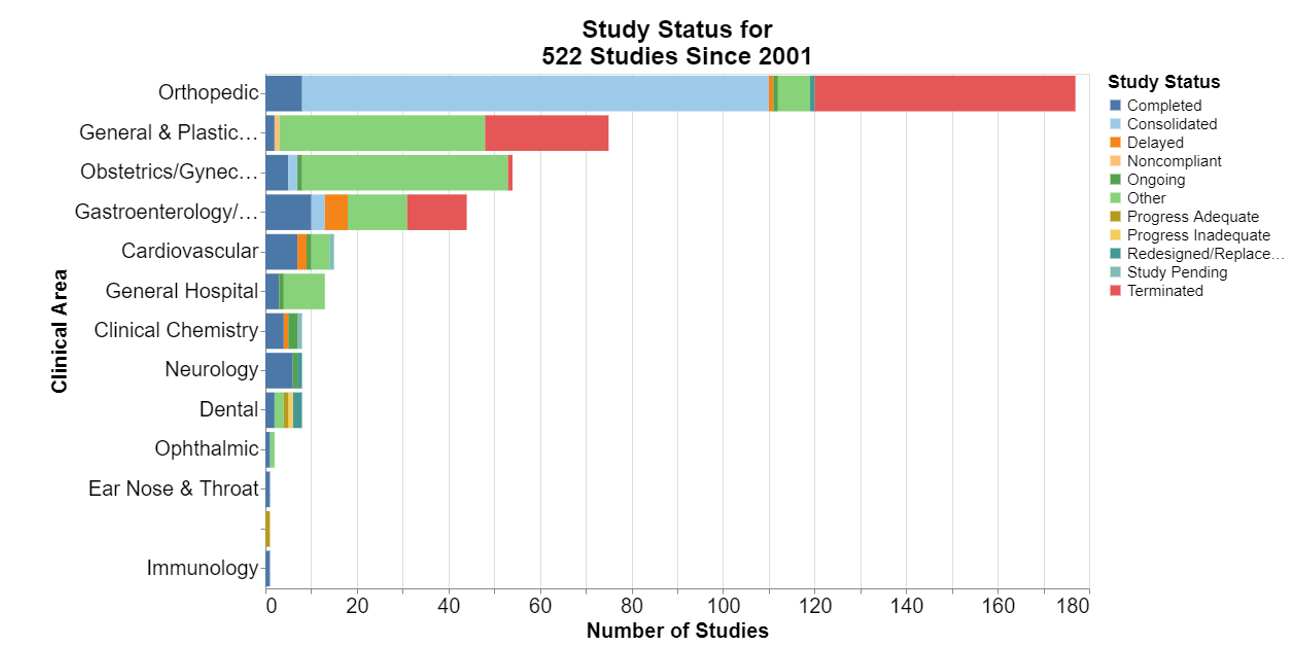

This chart is a bit disappointing because of the large green section for “other.” What the heck is that? It appears that FDA is in the process of transforming this database from old study status terms to newer terms laid out in the guidance document. The guidance says FDA will be shifting its vernacular to terms like “plan pending,” “plan overview,” “surveillance pending,” “ongoing” and so forth. But none of that is in the database yet.

There are some terms from the new guidance, including “terminated,” which means a manufacturer has not fulfilled or cannot fulfill the postmarket surveillance requirement identified in the 522 order (i.e., postmarket surveillance questions are no longer relevant, dataset cannot address public health question(s) in 522 order), and after all appropriate efforts to fulfill the requirement have been exhausted, FDA has terminated the postmarket surveillance requirement. Apparently, many of the 2011 orthopedic studies were terminated.

Many of the other 2011 orthopedic studies were consolidated. That means the manufacturer has requested to consolidate multiple 522 orders for devices of a particular device type into one consolidated 522 study and FDA has agreed to have the multiple 522 orders consolidated under one 522 order.

Surprisingly few of any of the studies were completed.

Finally, what study design and analysis are typically required?

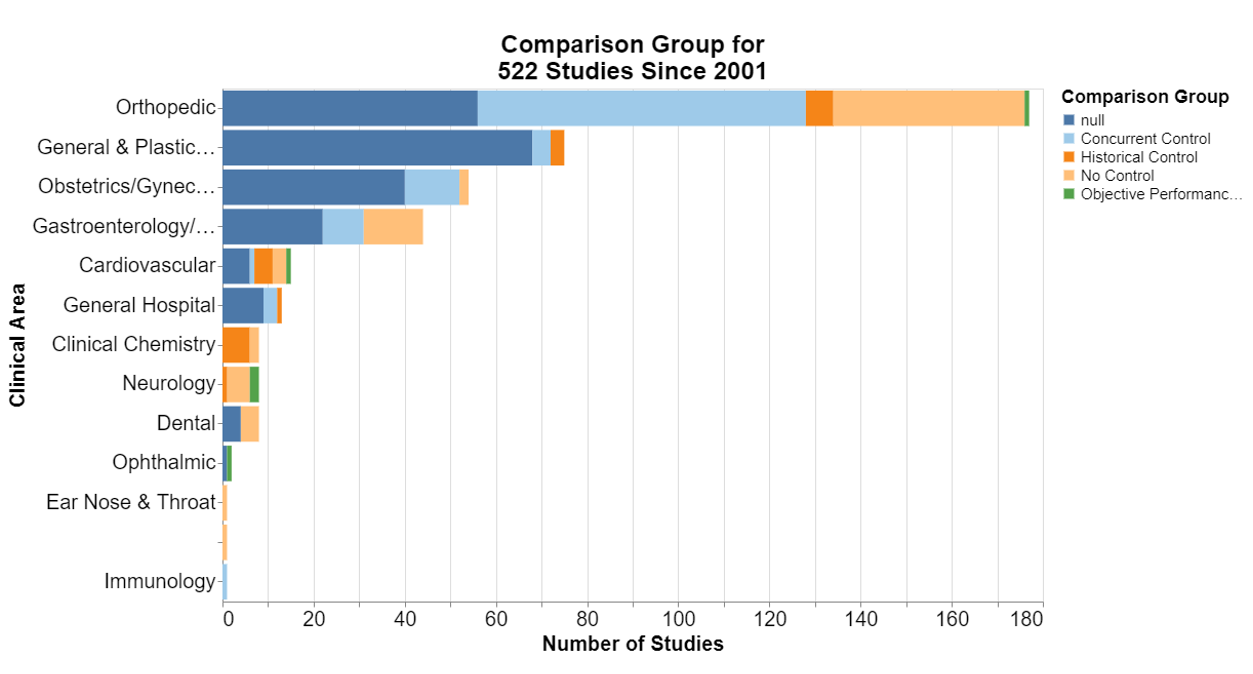

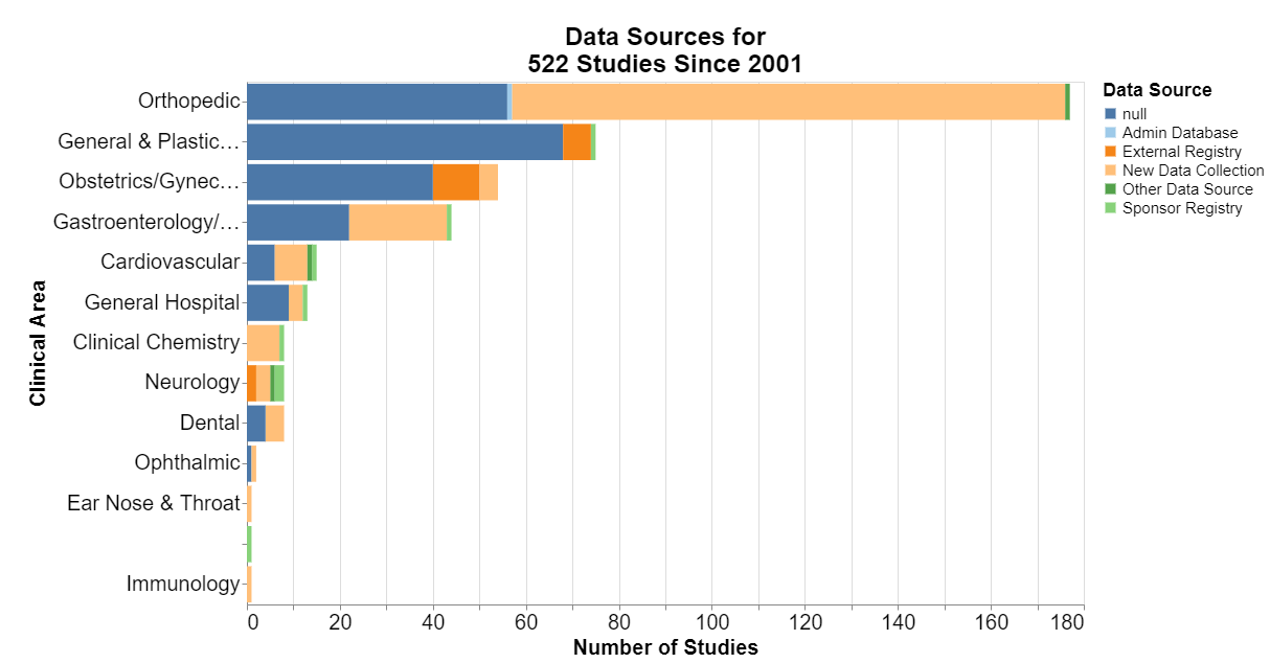

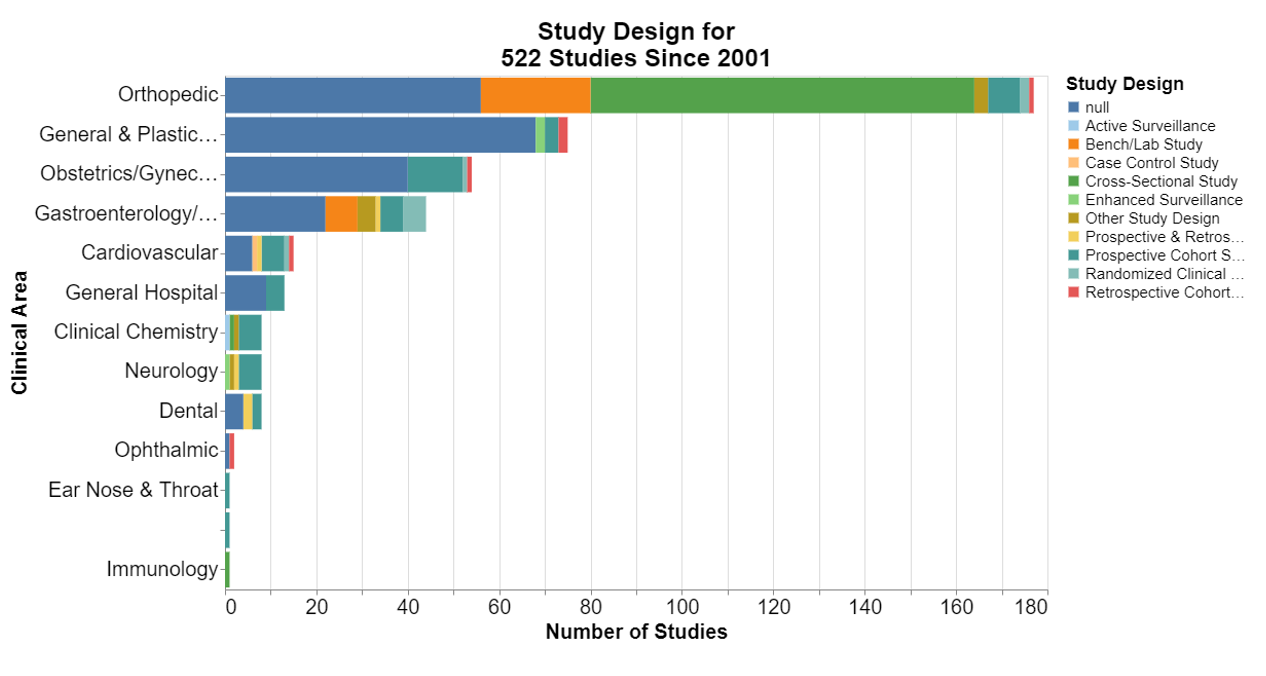

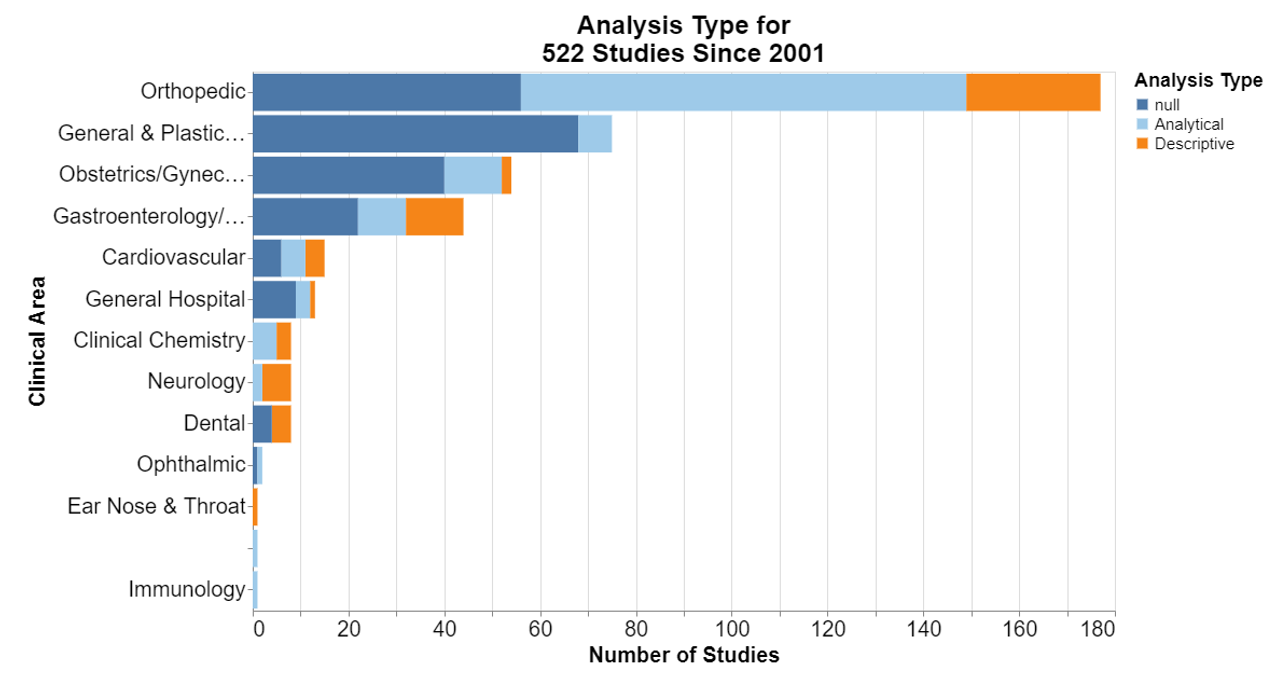

In each of the following, null means that the database did not include information for that field.

Here, frankly, I was interested that in the number of the studies where no control is required. I’m not a scientist, but it does seem particularly difficult sometimes to think of a concurrent control for a device already on the market. I was a little disappointed that historical controls are not more accepted.

New data collection is predominant. That should not be surprising because it seems to be the deliberate focus of postmarket surveillance studies to collect new data to inform the FDA decision-making.

At least in the orthopedic realm, it appears FDA was open to cross-sectional studies. The guidance explains that a cross-sectional study is a study in which the presence or absence of an exposure and health outcome are assessed at the same point in time.

More broadly, cross-sectional studies are observational studies that analyze data from a population at a single point in time. They are often used to measure the prevalence of health outcomes, understand determinants of health, and describe features of a population. Unlike other types of observational studies, cross-sectional studies do not follow individuals up over time. They are usually inexpensive and easy to conduct. That seems practical for devices that have been on the market for some time.

The guidance document lists each of these study design terms and provides a definition.

Interestingly, the guidance specifies that the general surveillance plan parameters need to include the analysis type, but it doesn’t define what that means. The CDC explains the difference here. Descriptive studies generate a hypothesis and answer what, who, where and when. Analytical studies test a hypothesis and answer why and how.

Conclusion

In general, I was disappointed that the data FDA shares are not more inclusive of such important data as the date a study concluded and the number of patients enrolled. The history of FDA’s 522 orders seems to be one of ups and downs, with the period from 2011 through 2013 representing its high point. More recently, 522 orders have fallen into disuse, even despite the fact that FDA published a new final guidance in 2022.

My understanding from clients over the years is that postmarket studies are hard. Once a product is commercially available, users frankly don’t want to mess with such studies, and such studies are hard to design in such a manner that they are meaningful. When I hear companies talk to FDA about wanting a faster path to market in exchange for more postmarket studies, honestly, I cringe. Most companies that have sought that have in my experience later regretted it. It’s also unclear to me what real value FDA derives from these data. But there’s no way I can really evaluate that from the publicly available data set.

* * * *

The Unpacking Averages® blog series digs into FDA’s data on the regulation of medical products, going deeper than the published averages. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s). Subscribe to this blog for email notifications.