FDA’s January 3, 2024, Federal Register notice soliciting comments on the agency’s plan to implement best practices for guidance development got me thinking. What do the data show regarding FDA’s performance in moving proposed guidance to final?

If you haven’t read it, the Federal Register notice explains that the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 directs FDA to issue a report identifying best practices for the efficient prioritization, development, issuance, and use of guidance documents and a plan for implementing those practices. The comment period on FDA’s draft report closed yesterday, March 4.

The agency’s draft report and plan, which was published separately, builds on a similar plan FDA released in 2011. As a result, in the data analysis below, I use 2011 as a start date, because that’s when the agency says it started to implement new approaches to guidance development.

Right up front, I want to be transparent about a significant personal interest I have in the topic of FDA guidance. While I will explain more below, I filed the Citizens Petition in May 1995 that resulted in FDA adopting the Good Guidance Practices or GGPs. Indeed, I coined that term, wanting FDA to feel convicted because of its constant urging to industry that companies adopt GXP in manufacturing, clinical research and other areas. I think the term GGP had its intended effect.

Results

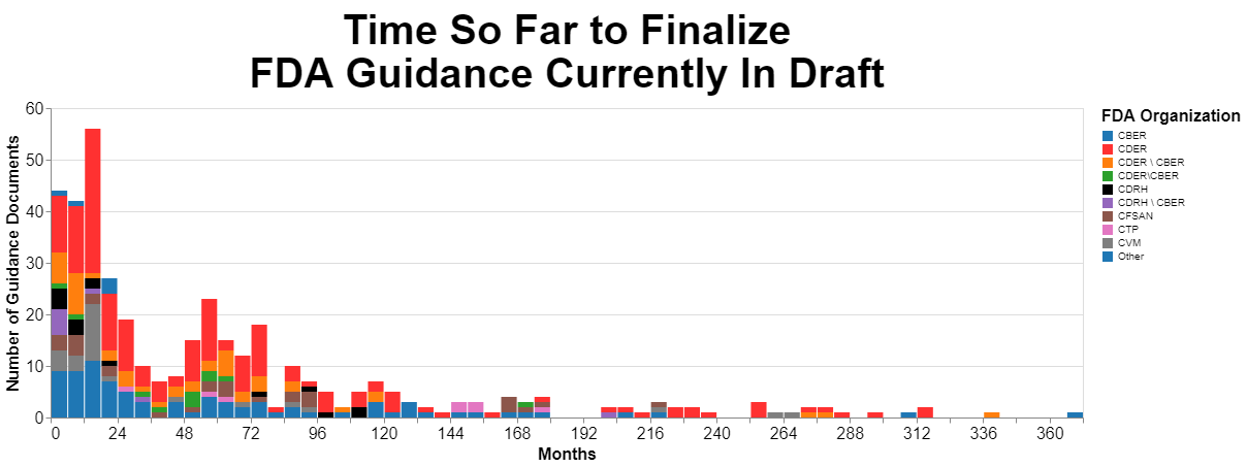

To start, let’s analyze how long currently proposed guidance documents have been in that limbo, not having been finalized. Here are the results measured in months:

Originally, I prepared that chart using days as a measure, but the numbers made my head hurt so I converted them to months. I broke the data down by originating center as much as possible, but there’s quite a few guidances that are developed by multiple centers together.

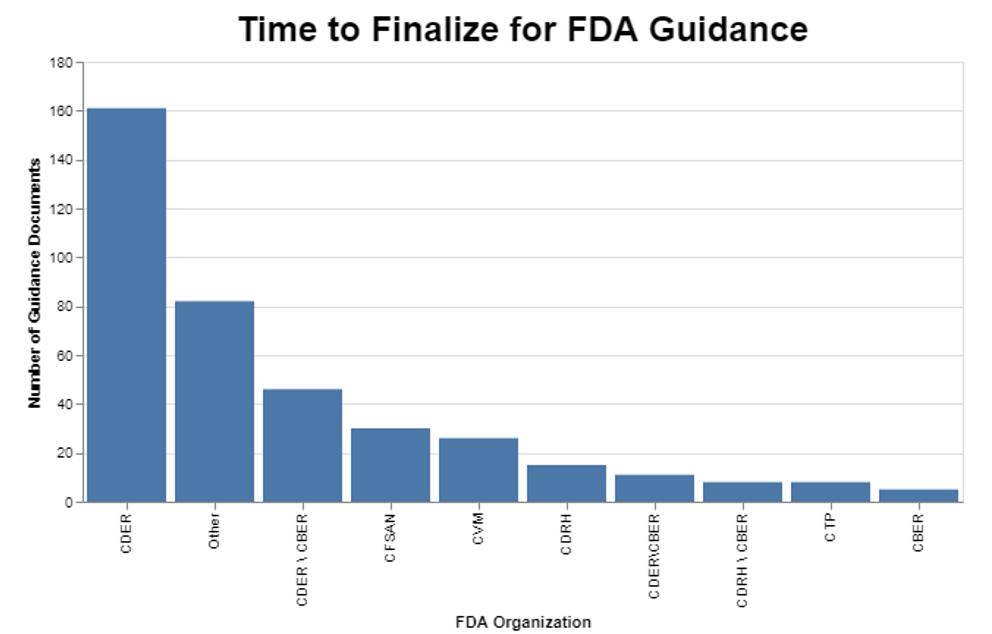

I then wanted to break the data down further to see if the originating center had any impact on the amount of time it was taking to finalize those guidance documents. Turns out there is wide variability among centers.

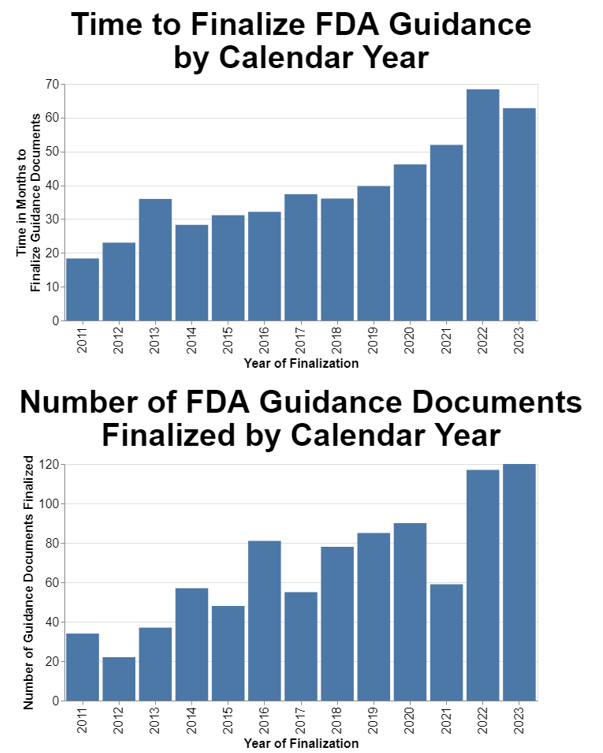

I then wondered how FDA performance had changed over time. To do this part of the analysis, I decided to only analyze final guidance that are still in effect. I omitted any guidance that might’ve been finalized at one time, but then withdrawn.

As I already mentioned, I selected 2011 as my start date since that’s when the agency says it began implementing reforms to its guidance process. I also chose calendar years because frankly that’s more meaningful to the public.

In presenting this data, I also thought it relevant to include the volume of guidance documents in case that’s a factor in FDA performance. I chose to measure the volume in terms of guidance finalized in a given year, as opposed to, for example, proposed in a given year. Finalization is the ultimate goal.

The data show a clear trend toward the increasing amount of time it takes to finalize guidance. The data also show a trend toward FDA finalizing more guidance each year.

Methodology

FDA maintains a searchable list of guidance documents that I used as my starting point. On the date I searched the database for this analysis (January 29, 2024), there were 2108 guidance documents. I limited my search to documents that FDA characterized as “guidance documents,” which excludes such other things as Compliance Policy Guides, information sheets, industry letters, concept papers and a variety of other miscellaneous agency documents. In total, there were over 2700 documents in the database including these other items at that time.

The database includes a field for whether the document is draft or final, so for the first chart I limited my search to those that the agency said were draft. The data set also included the issue date, so the calculation was quite simple to determine the amount of time between the issue date and February 1, 2024, the date on which I was doing the analysis. As I said, I initially did the analysis in days, but when the numbers were huge, I divided those numbers by 30 to approximate the time by months.

The only laborious task was coming up with a way to identify the appropriate center. As I mentioned above, there were quite a few instances where an individual guidance document was developed by multiple centers working together, or with various offices within the Office of the Commissioner. Thus, the original list of entities was quite long. I went through the results to figure out which organizations were responsible for the lion’s share of the guidance, and came up with the list you see in the chart. My goal was to drive the “Other” category as small as possible. It turns out, for example, that the combination of CDER and CBER was responsible for quite a few.

For the charts showing the length of time between publishing draft and final guidance, as I mentioned above, I used as my starting point the existing data set of final guidance. This excludes, as mentioned, guidances that might’ve been previously finalized but withdrawn.

The only data point missing from the FDA database for final guidance is the date on which the draft guidance was published. Fortunately, that data is readily available on regulations.gov. I searched regulations.gov to come up with the draft publication date for each of the finalized guidance documents.

That repository started in 2002. I noticed that some of the early entries in regulations.gov were suspicious regarding the dates, but since I focused on the years 2011 forward, those data seem to be more reliable.

Statement of Interest

I am an industry attorney, but I think it’s important to include a statement of interest where I have a particular relationship beyond my general relationship with manufacturers regulated by FDA. Initially for the Indiana Medical Device Manufacturers Council but eventually on behalf of a broad coalition of major trade associations in the food, drug, medical device, and veterinary medicine industries, 30 years ago I sought reform in the way FDA gives guidance to the regulated industries. Prior to 1995, FDA had a very helter-skelter system through which companies often couldn't even find relevant guidance documents, and FDA had a penchant for announcing new policy from the podium. Many of the guidance documents did not receive public input, and sometimes were poorly conceived.

I filed the citizen's petition at FDA referenced above requesting that the agency adopt “Good Guidance Practices.” I testified before Congress and at an FDA hearing, explaining the challenges faced by industry and offering proposed improvements. FDA adopted a regulation in 21 CFR 10.115 implementing the GGPs, and in 1997 as a part of FDAMA, Congress required FDA to observe GGPs. In 2005, OMB proposed and in 2007 adopted GGPs for all federal agencies.

While the government’s use of guidance is a very important topic to me, no one is paying me to do this analysis.

Interpretation

FDA frankly faces a legal problem here. Under the GGPs, draft guidances are placed on FDA’s website for one purpose and one purpose only, to facilitate public comment. Once the comment period closes, FDA has no legal reason to keep the draft guidance on its website. The agency is no longer taking comments. Draft guidance documents should come off the website as soon as the comment period is over, and their purpose is served.

Leaving draft guidance on the FDA’s website must be understood to serve a different purpose than collecting comments, a purpose that is not legally justified. Draft guidance documents that remain on the agency’s website after the close of the comment period is strong evidence that FDA in reality is trying to “implement” the draft guidance document, something the agency is expressly prohibited from doing by 21 CFR 10.115(g)(iv)(D).

In less legalistic terms, a draft is merely a draft, and the whole purpose of vetting it through public comment is to identify problems with the draft and improve it. Implementing a draft that by definition reflects no public input means that the agency is effectively bypassing public comment. Thus, the violation.

This is much like FDA’s argument when a clinical trial press release remains on a website too long, such that FDA argues that is no longer there to share new scientific information but rather for a commercial purpose. FDA periodically argues that news is only news when it’s new.

The data above show the magnitude of FDA’s draft guidance problem. At least one draft guidance document is over 360 months old, which translated to years is over 30 years old. If there were just one outlier, there would not be a systemic problem. But there are draft guidance documents pretty much the entire spectrum between zero and 30 years. In fact, you will notice a distinct clump between four and six years old.

While it appears that CDER is by far the worst offender, it’s also clear that quite a few guidance documents that involve multiple centers age substantially before being put into final form. Intuitively, this is not surprising because when more than one center is involved, they may have different priorities, and they obviously need to work together, which for some reason is still a challenge.

But honestly, we need to lay the responsibility for this at the feet of the Office of the Commissioner. The centers do not operate as autonomous agencies, but all under the direction of the Commissioner. The Commissioner must take responsibility for getting joint projects done that cut across multiple centers.

FDA’s draft report notes that in certain centers, this has become a topic for user fee discussions, for example in CDRH. It seems apparent that those discussions are having an impact, as the delay at CDRH is among the lowest, approaching about 1.5 years on average. A case could be made that certain types of guidance, in particular those that help industry understand how to get products approved more quickly, could benefit from industry resources. At the same time, FDA has a compliance responsibility that should not be tied to user fees.

The problem is clearly getting worse on average for the agency as a whole. Across a dozen years, the delays in finalizing guidance went from on average under 20 months to on average over 60 months. That’s just not acceptable.

I included the separate chart on the number of guidances finalized because I did wonder if at least in part this trend is caused by an increase in the volume of guidance. The trend toward increased numbers of guidance documents being finalized is distinctly upward, although not as dramatic as the increase in delays in guidance finalization.

We should not be comforted by this data. Producing more guidance at the expense of substantial delays in finalizing the guidance perverts the system. To speak plainly, unless draft guidance is misused to convey present FDA’s thinking now, it is literally worthless until finalized. The only way it has any value at all is if the parties misuse it and treat it as present guidance even though draft.

The system was never intended to work that way. Draft was just an intermediate step toward finalization, and all the value was in the final draft. Draft guidance is literally raw thinking without the benefit of public comment. It was never intended to be an end point.

Conclusion

While substantially improved from what it was 30 years ago, FDA’s current guidance process leaves a lot to be desired. I outlined in a series of three blog posts—here, here, and here—a series of problems and reforms that I hope FDA considers. The problem I highlight in this post is simply one of many, the agency’s growing tendency to leave guidance in draft form literally for years.

In its draft report, FDA perhaps not surprisingly seems to focus on changes that might save itself time and money. That’s not a bad thing; it’s just not the whole picture. Section 2505(a)(2)(C) of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 specifically requires FDA to develop a plan for “implementing innovative guidance development processes and practices.” That’s a much broader directive than simply saving the agency some time and money.

In my blog post series, I support reimagining the whole guidance process, incorporating software tools that were not available 30 years ago when the GGPs were published. FDA is stuck in antiquated procedures, and seems to only be focusing on minor improvements that might save money. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 directed FDA to consider innovative solutions, and in that regard, the draft report fails completely. The agency engages in only minor tweaking of a fundamentally broken system.

* * * *

The Unpacking Averages® blog series digs into FDA’s data on the regulation of medical products, going deeper than the published averages. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s). Subscribe to this blog for email notifications.